MADE IN CHINA – photobook

Details

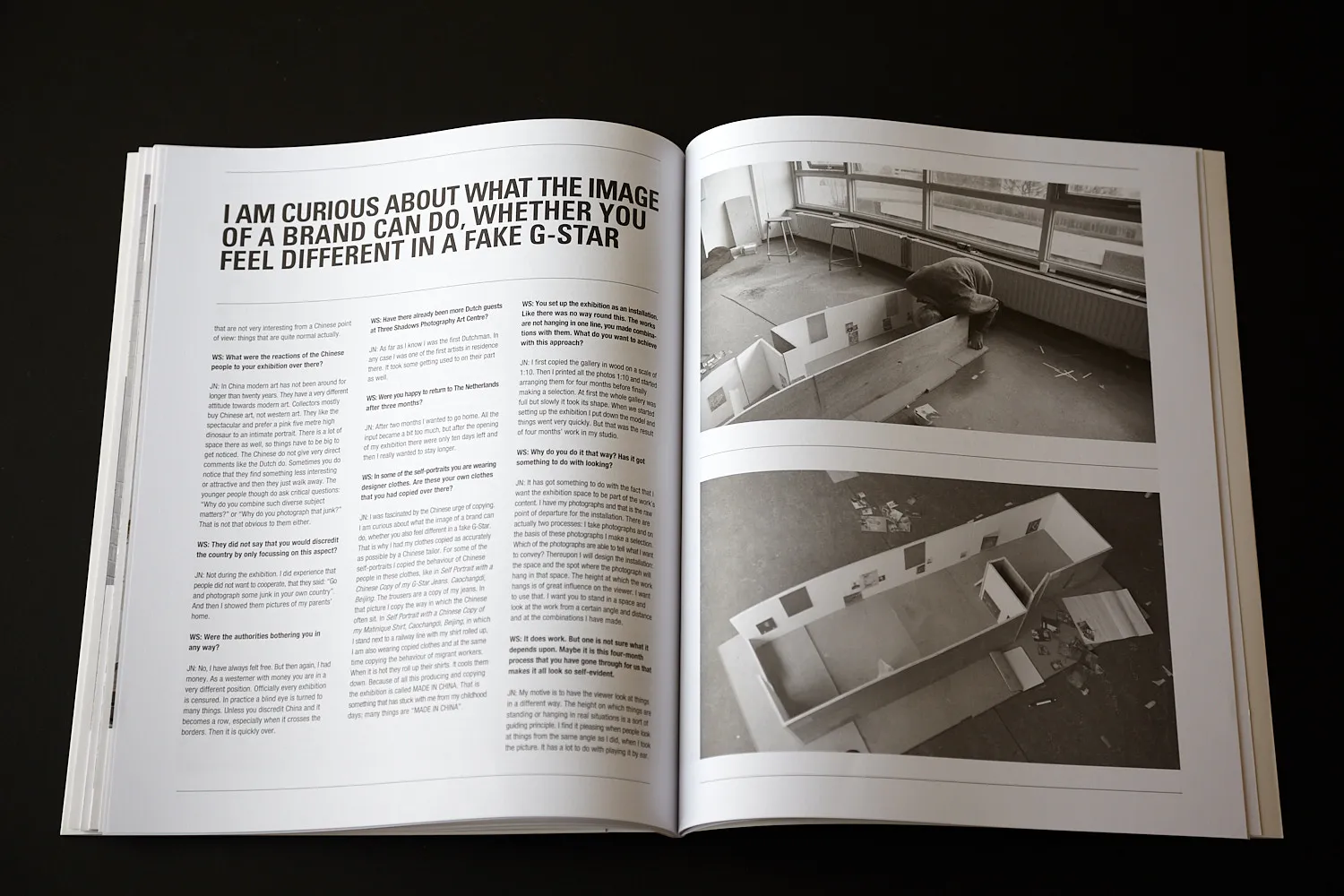

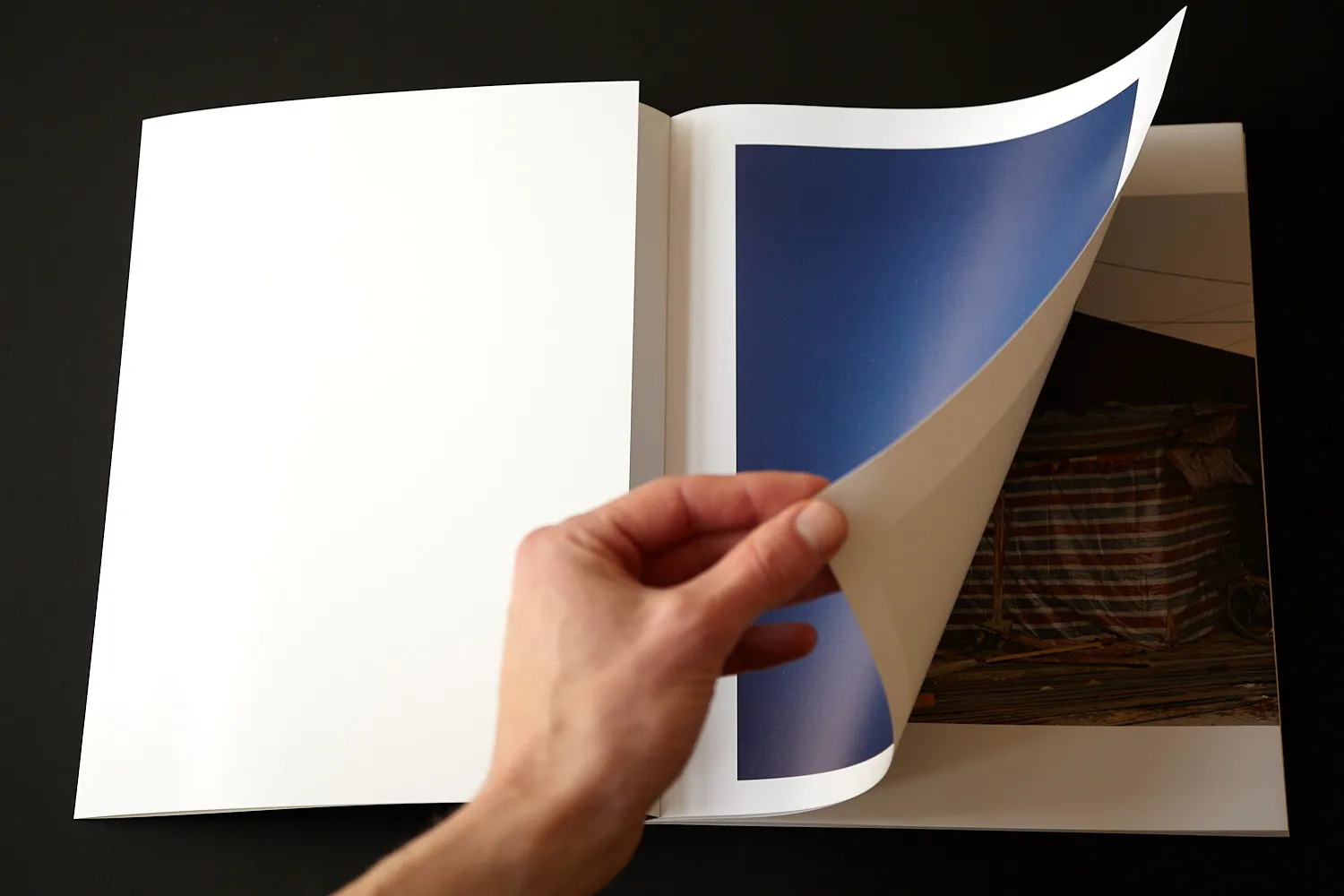

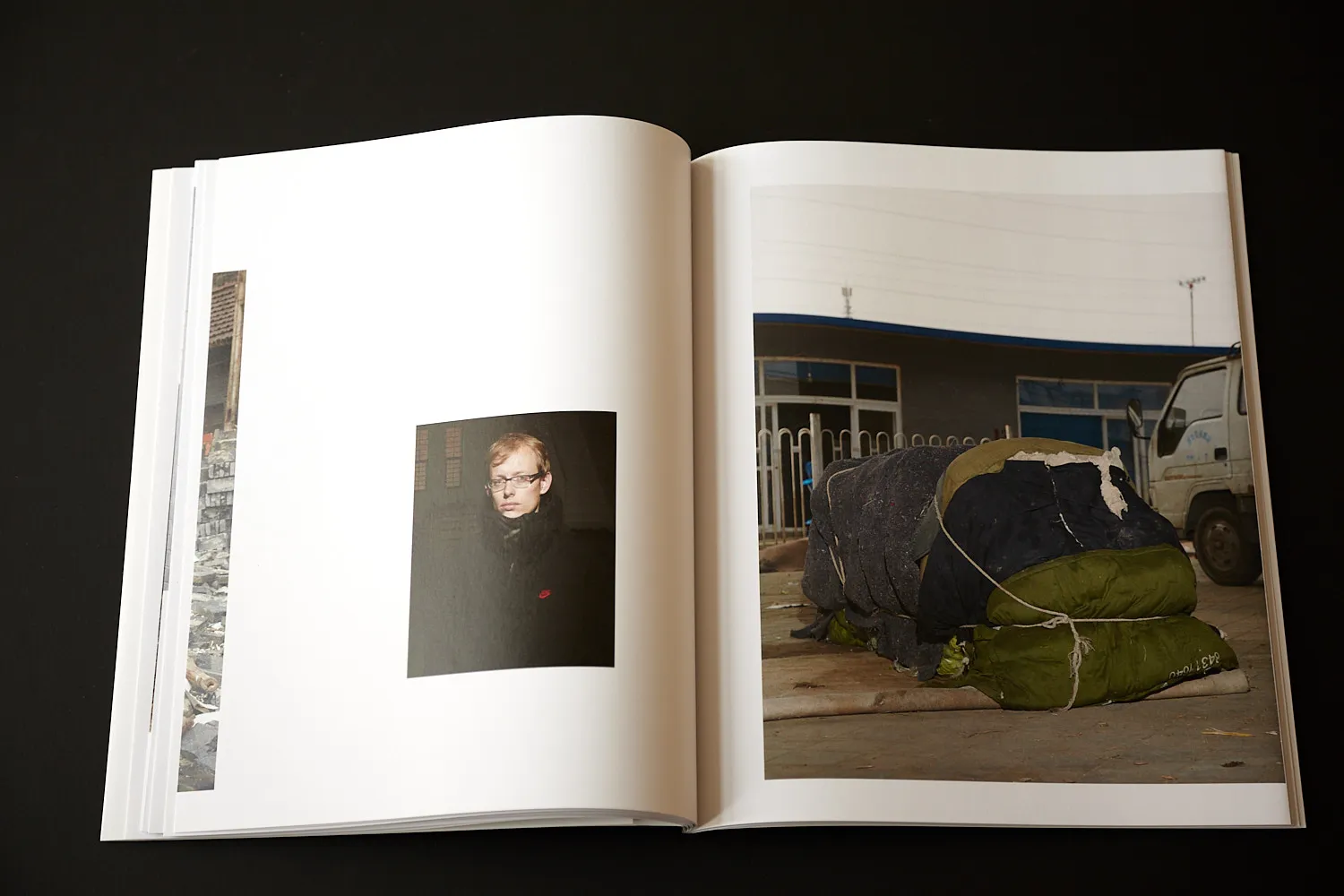

MADE IN CHINA is the result of Johan Nieuwenhuize’s artist in residency period at the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing in 2009. Nieuwenhuize took pictures in the homes of migrant workers in the area of Caochangdi and combines these still lifes with abstract pictures of the sky and self portraits.

The project was shown in solo exhibitions at the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing, in 2009, at Van Kranendonk Gallery and Art Rotterdam, both in 2010.

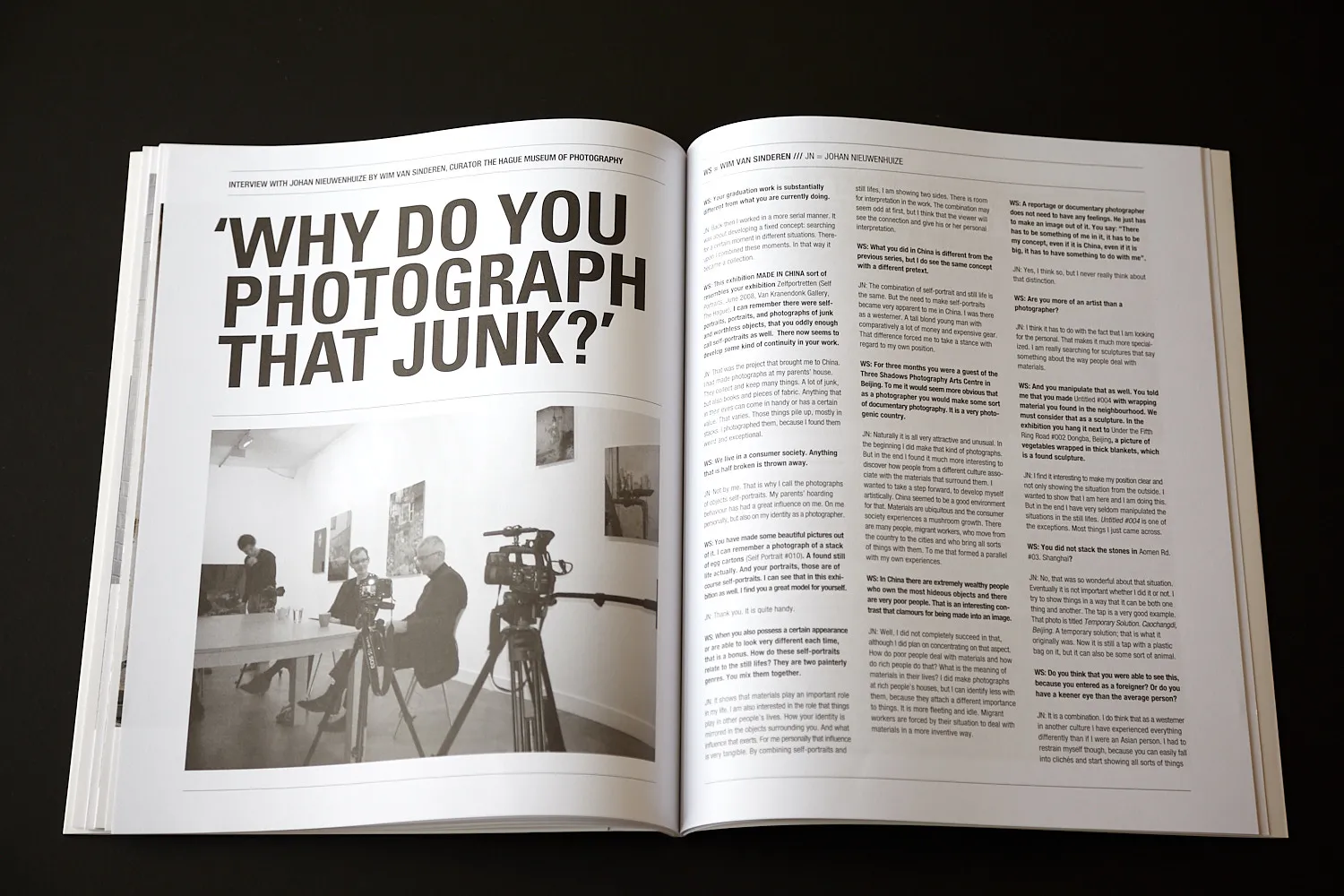

The book MADE IN CHINA was self-published in 2011 and contains a text by Hripsimé Visser, then conservator of photography of Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and an interview by Wim van Sinderen, then senior curator GEM/The Hague Museum of Photography. This text can be read below.

MADE IN CHINA was made possible by the Mondriaan Fund and The Shareholders.

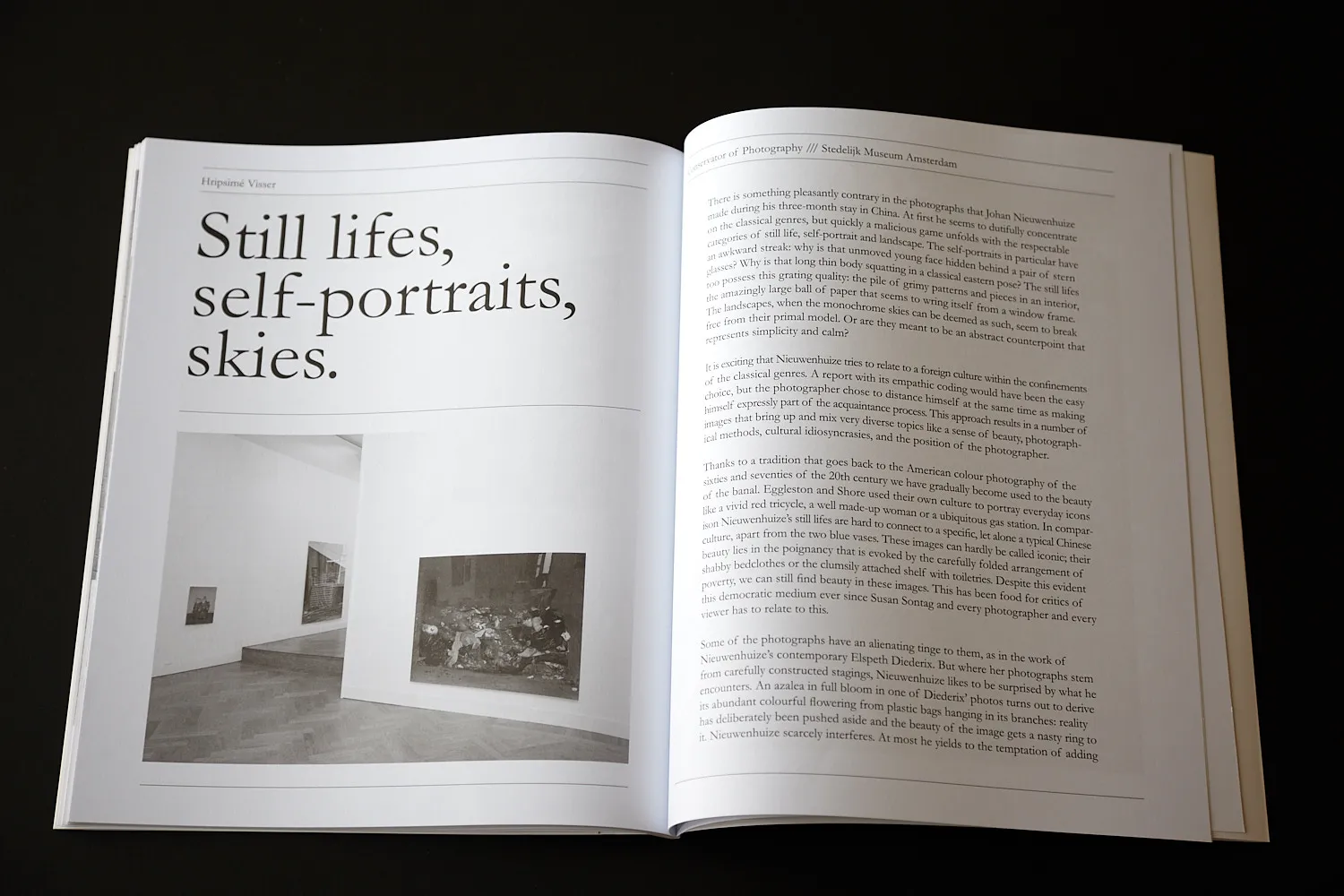

Still lifes, self-portraits, skies.

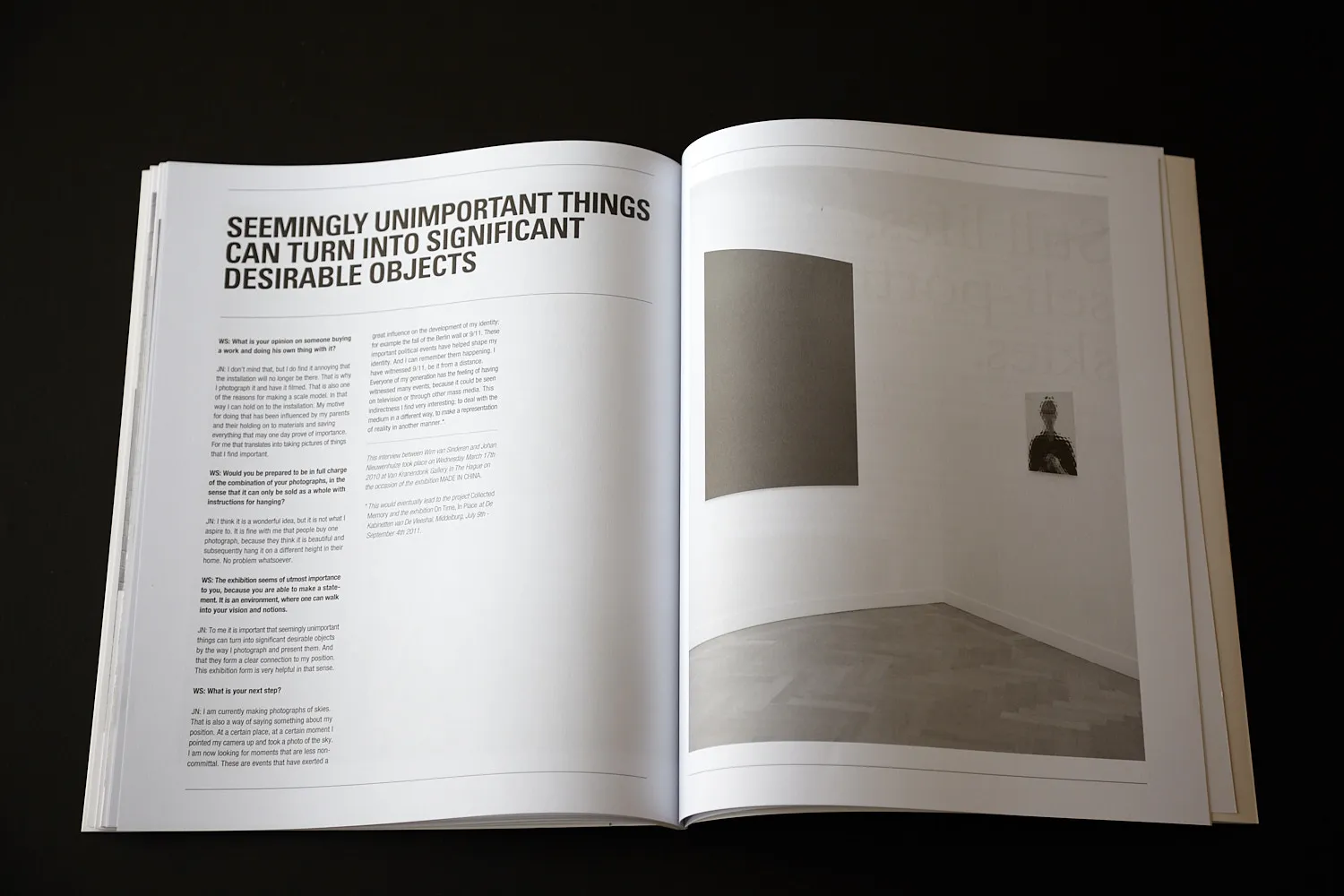

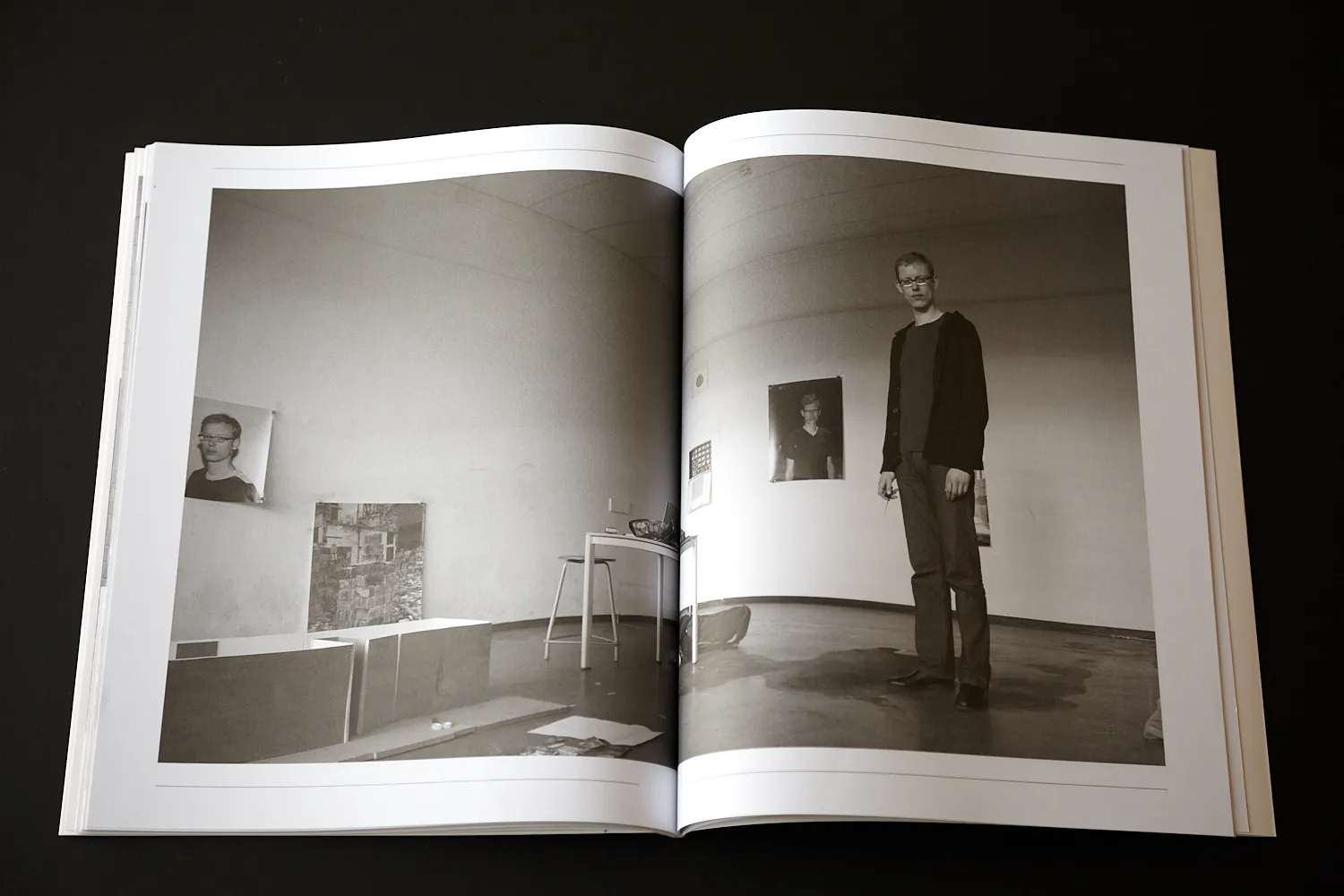

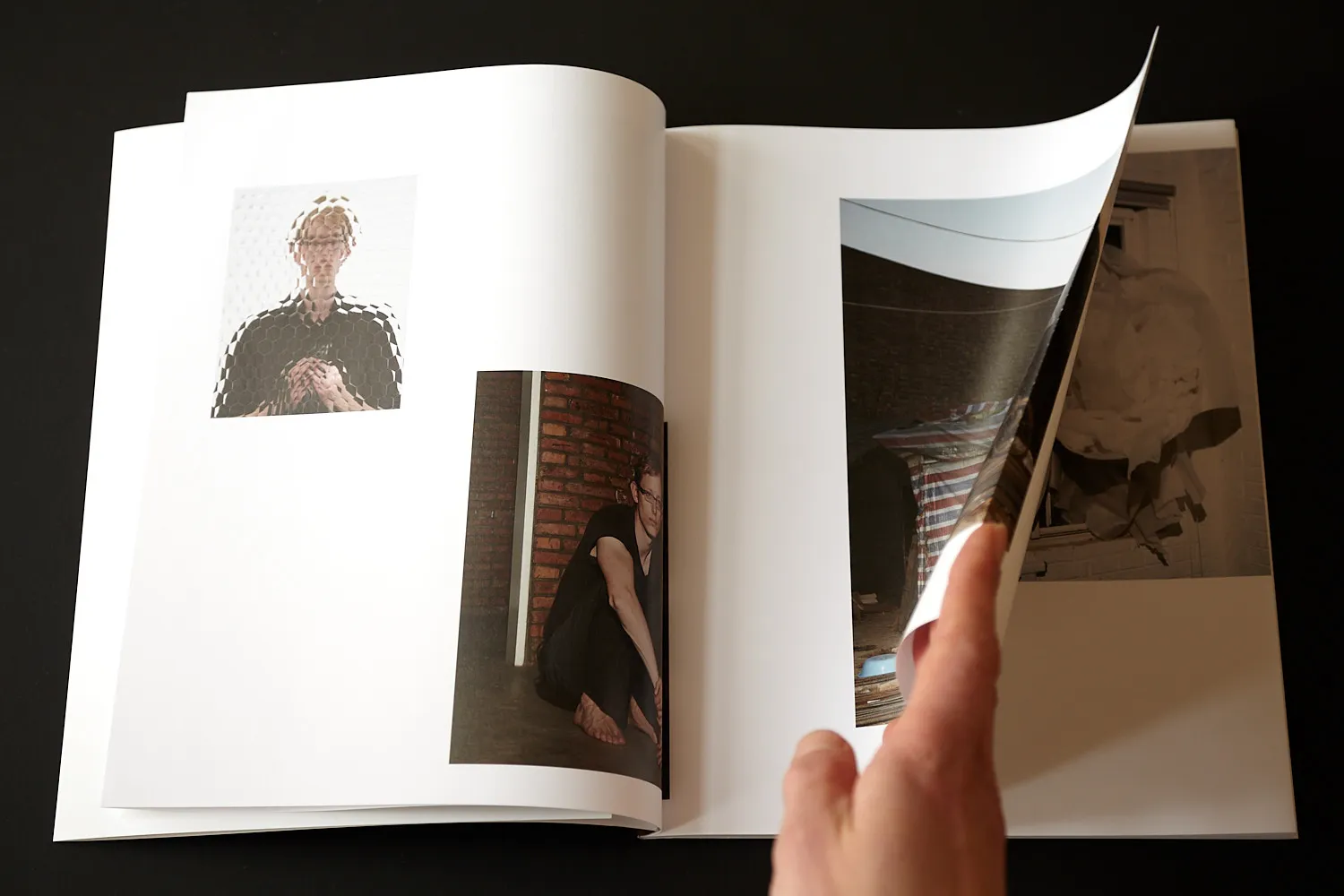

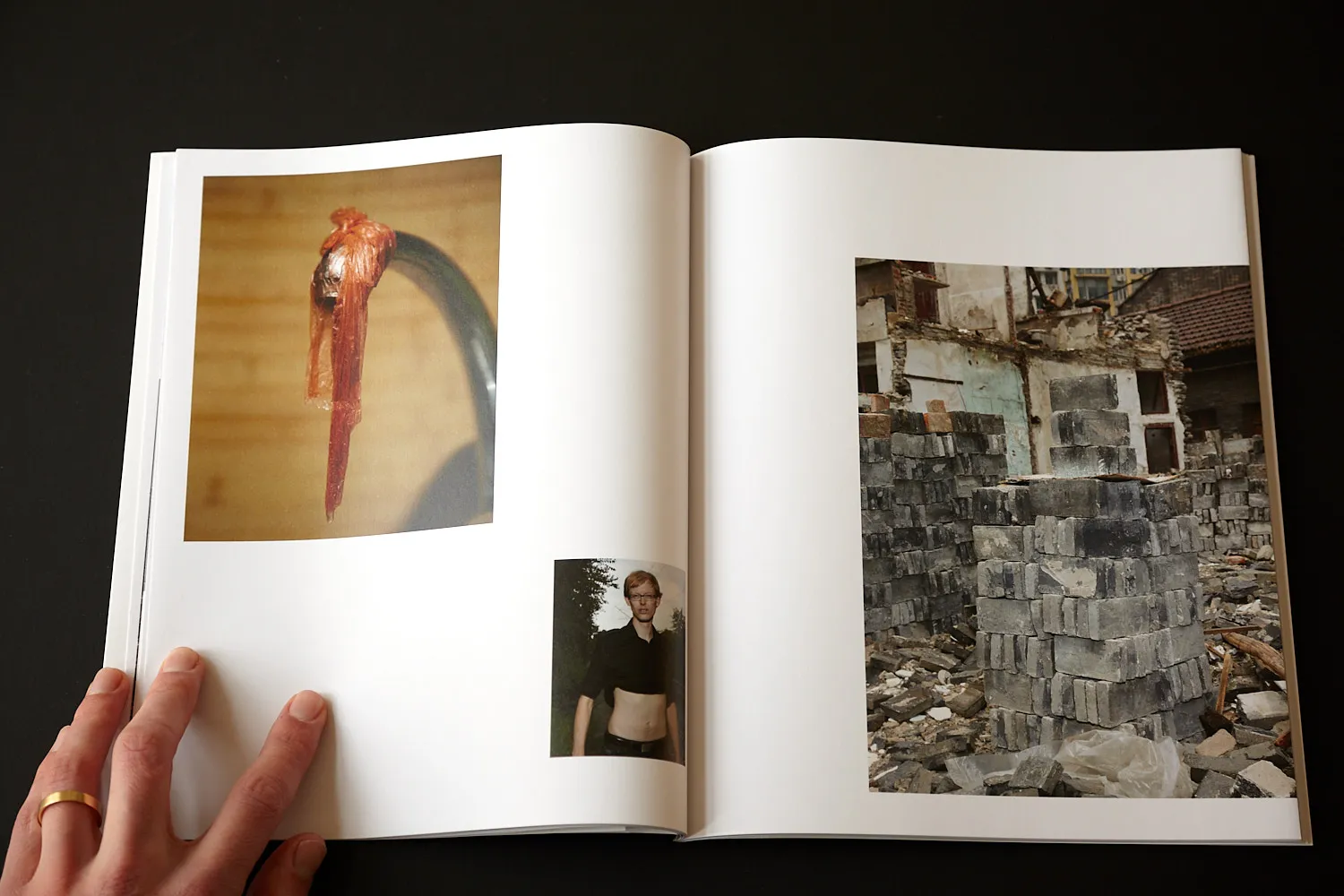

There is something pleasantly contrary in the photographs that Johan Nieuwenhuize made during his three-month stay in China. At first he seems to dutifully concentrate on the classical genres, but quickly a malicious game unfolds with the respectable categories of still life, self-portrait and landscape. The self-portraits in particular have an awkward streak: why is that unmoved young face hidden behind a pair of stern glasses? Why is that long thin body squatting in a classical eastern pose? The still lifes too possess this grating quality: the pile of grimy patterns and pieces in an interior, the amazingly large ball of paper that seems to wring itself from a window frame. The landscapes, when the monochrome skies can be deemed as such, seem to break free from their primal model. Or are they meant to be an abstract counterpoint that represents simplicity and calm?

It is exciting that Nieuwenhuize tries to relate to a foreign culture within the confinements of the classical genres. A report with its empathic coding would have been the easy choice, but the photographer chose to distance himself at the same time as making himself expressly part of the acquaintance process. This approach results in a number of images that bring up and mix very diverse topics like a sense of beauty, photographical methods, cultural idiosyncrasies, and the position of the photographer.

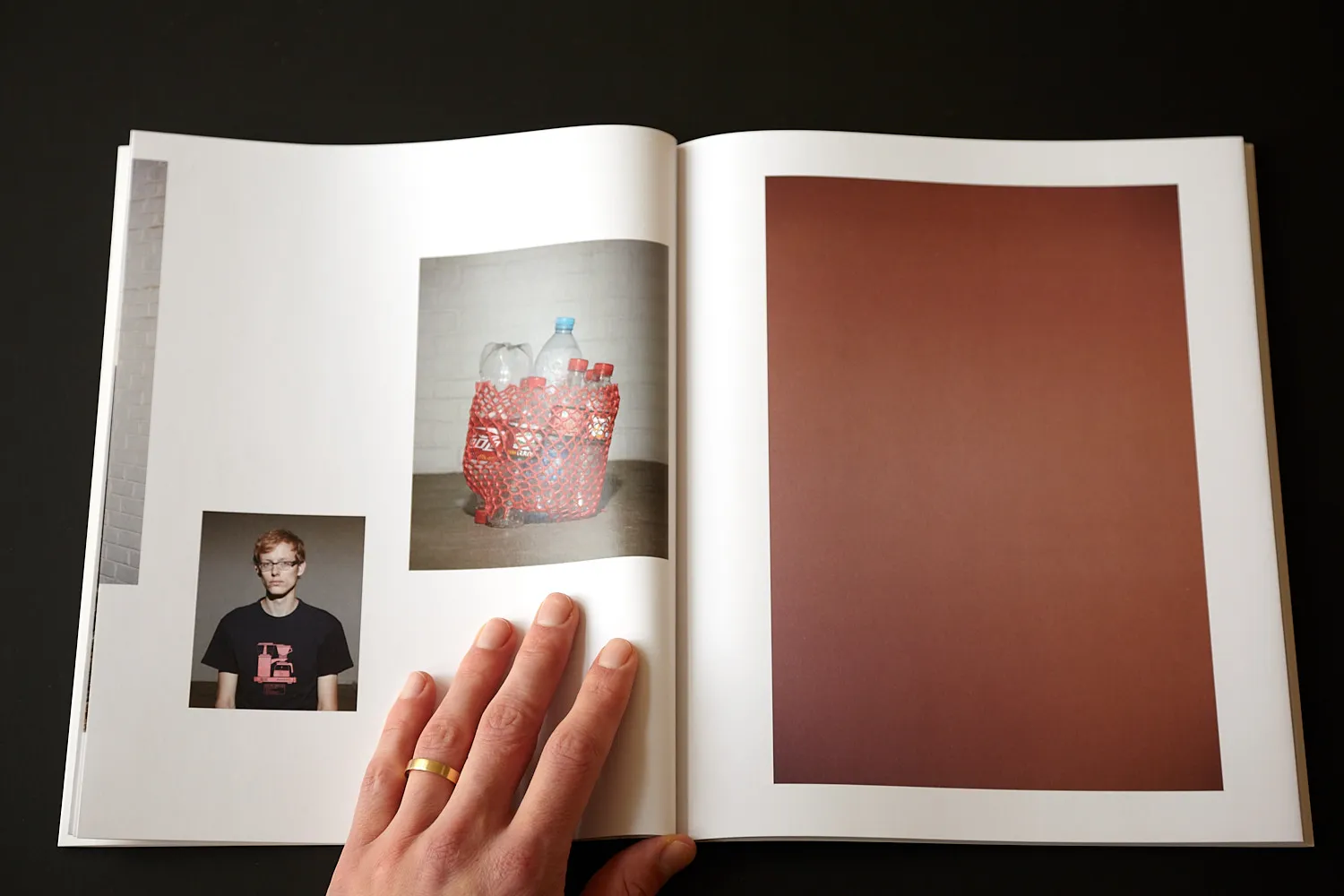

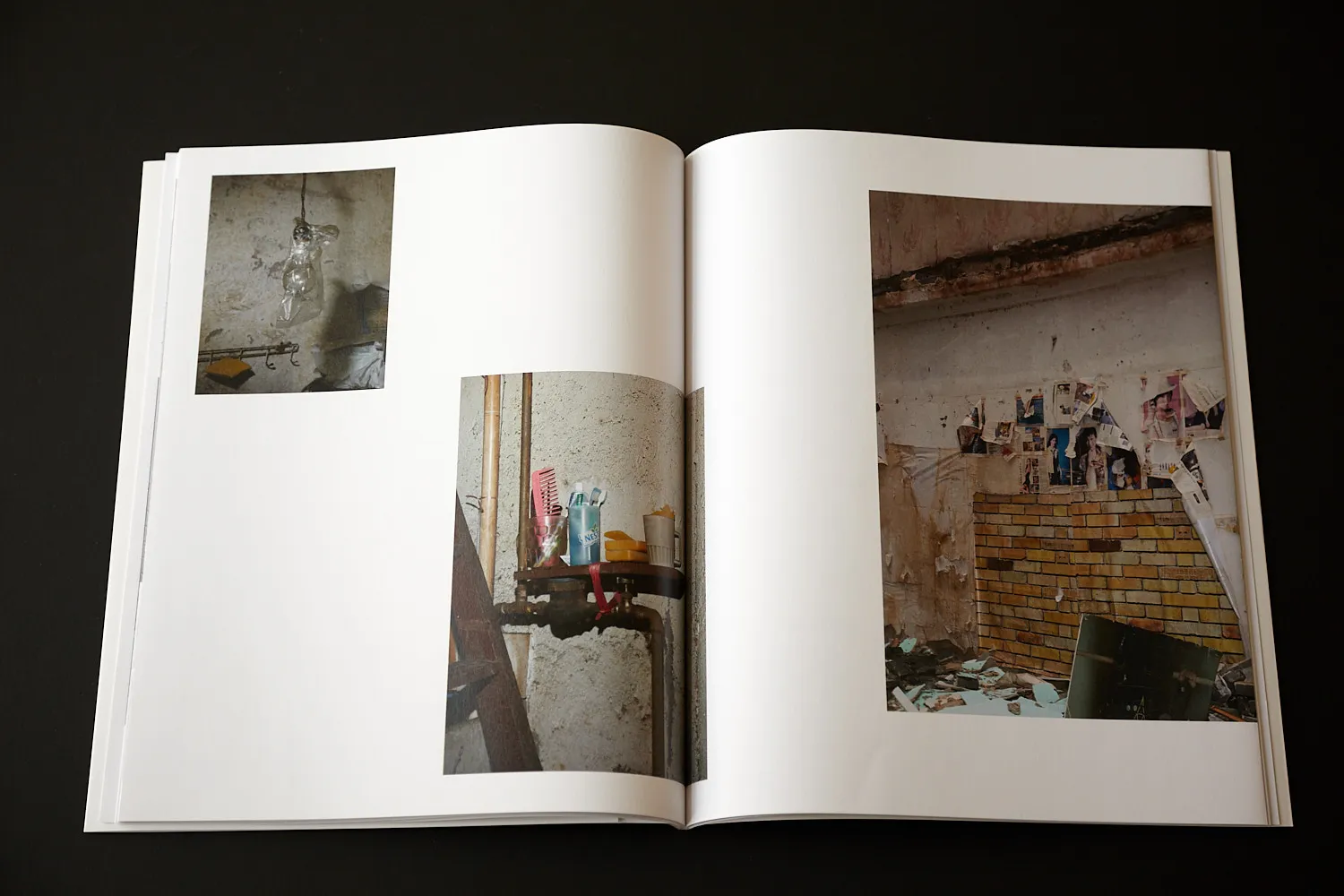

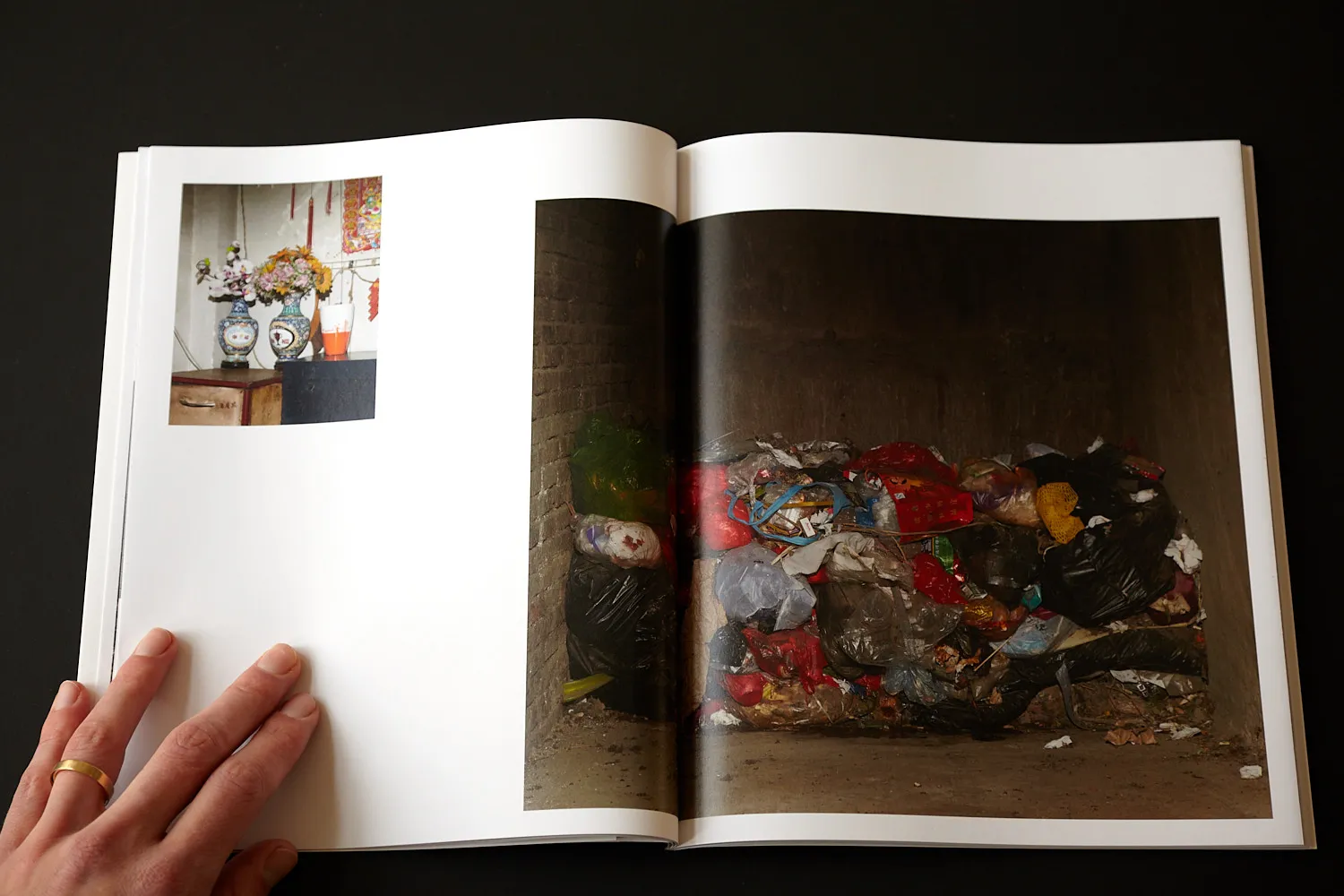

Thanks to a tradition that goes back to the American colour photography of the sixties and seventies of the 20th century we have gradually become used to the beauty of the banal. Eggleston and Shore used their own culture to portray everyday icons like a vivid red tricycle, a well made-up woman or a ubiquitous gas station. In comparison Nieuwenhuize’s still lifes are hard to connect to a specific, let alone a typical Chinese culture, apart from the two blue vases. These images can hardly be called iconic; their beauty lies in the poignancy that is evoked by the carefully folded arrangement of shabby bedclothes or the clumsily attached shelf with toiletries. Despite this evident poverty, we can still find beauty in these images. This has been food for critics of this democratic medium ever since Susan Sontag and every photographer and every viewer has to relate to this.

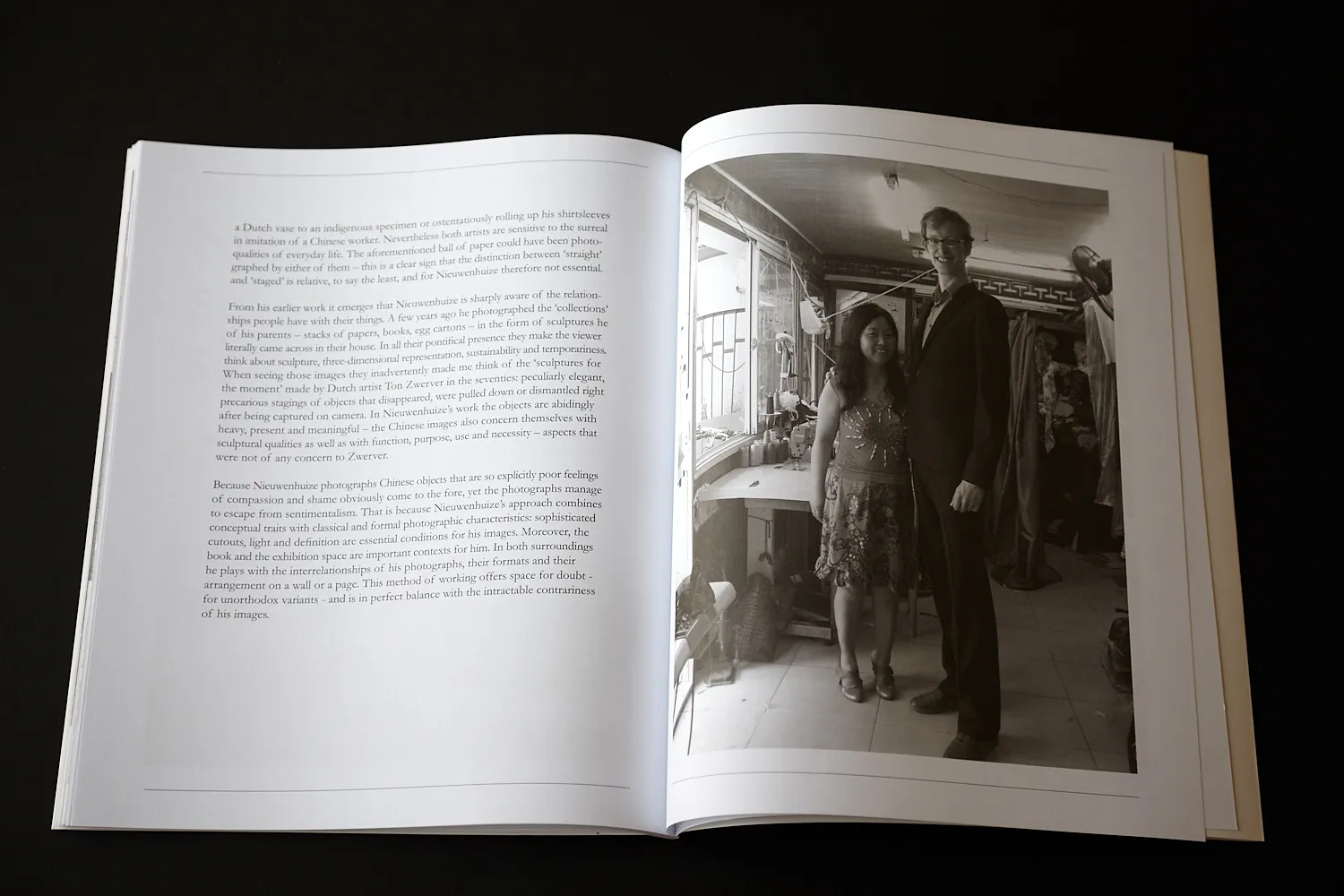

Some of the photographs have an alienating tinge to them, as in the work of Nieuwenhuize’s contemporary Elspeth Diederix. But where her photographs stem from carefully constructed stagings, Nieuwenhuize likes to be surprised by what he encounters. An azalea in full bloom in one of Diederix’ photos turns out to derive its abundant colourful flowering from plastic bags hanging in its branches: reality has deliberately been pushed aside and the beauty of the image gets a nasty ring to it. Nieuwenhuize scarcely interferes. At most he yields to the temptation of adding a Dutch vase to an indigenous specimen or ostentatiously rolling up his shirtsleeves in imitation of a Chinese worker. Nevertheless both artists are sensitive to the surreal qualities of everyday life. The aforementioned ball of paper could have been photographed by either of them – this is a clear sign that the distinction between ‘straight’ and ‘staged’ is relative, to say the least, and for Nieuwenhuize therefore not essential.

(…)this is a clear sign that the distinction between ‘straight’ and ‘staged’ is relative, to say the least, and for Nieuwenhuize therefore not essential.

From his earlier work it emerges that Nieuwenhuize is sharply aware of the relationships people have with their things. A few years ago he photographed the ‘collections’ of his parents – stacks of papers, books, egg cartons – in the form of sculptures he literally came across in their house. In all their pontifical presence they make the viewer think about sculpture, three-dimensional representation, sustainability and temporariness. When seeing those images they inadvertently made me think of the ‘sculptures for the moment’ made by Dutch artist Ton Zwerver in the seventies: peculiarly elegant, precarious stagings of objects that disappeared, were pulled down or dismantled right after being captured on camera. In Nieuwenhuize’s work the objects are abidingly heavy, present and meaningful – the Chinese images also concern themselves with sculptural qualities as well as with function, purpose, use and necessity – aspects that were not of any concern to Zwerver.

Because Nieuwenhuize photographs Chinese objects that are so explicitly poor feelings of compassion and shame obviously come to the fore, yet the photographs manage to escape from sentimentalism. That is because Nieuwenhuize’s approach combines conceptual traits with classical and formal photographic characteristics: sophisticated cutouts, light and definition are essential conditions for his images. Moreover, the book and the exhibition space are important contexts for him. In both surroundings he plays with the interrelationships of his photographs, their formats and their arrangement on a wall or a page. This method of working offers space for doubt – for unorthodox variants – and is in perfect balance with the intractable contrariness of his images.

Hripsimė Visser