MADE IN CHINA – photo series

Details

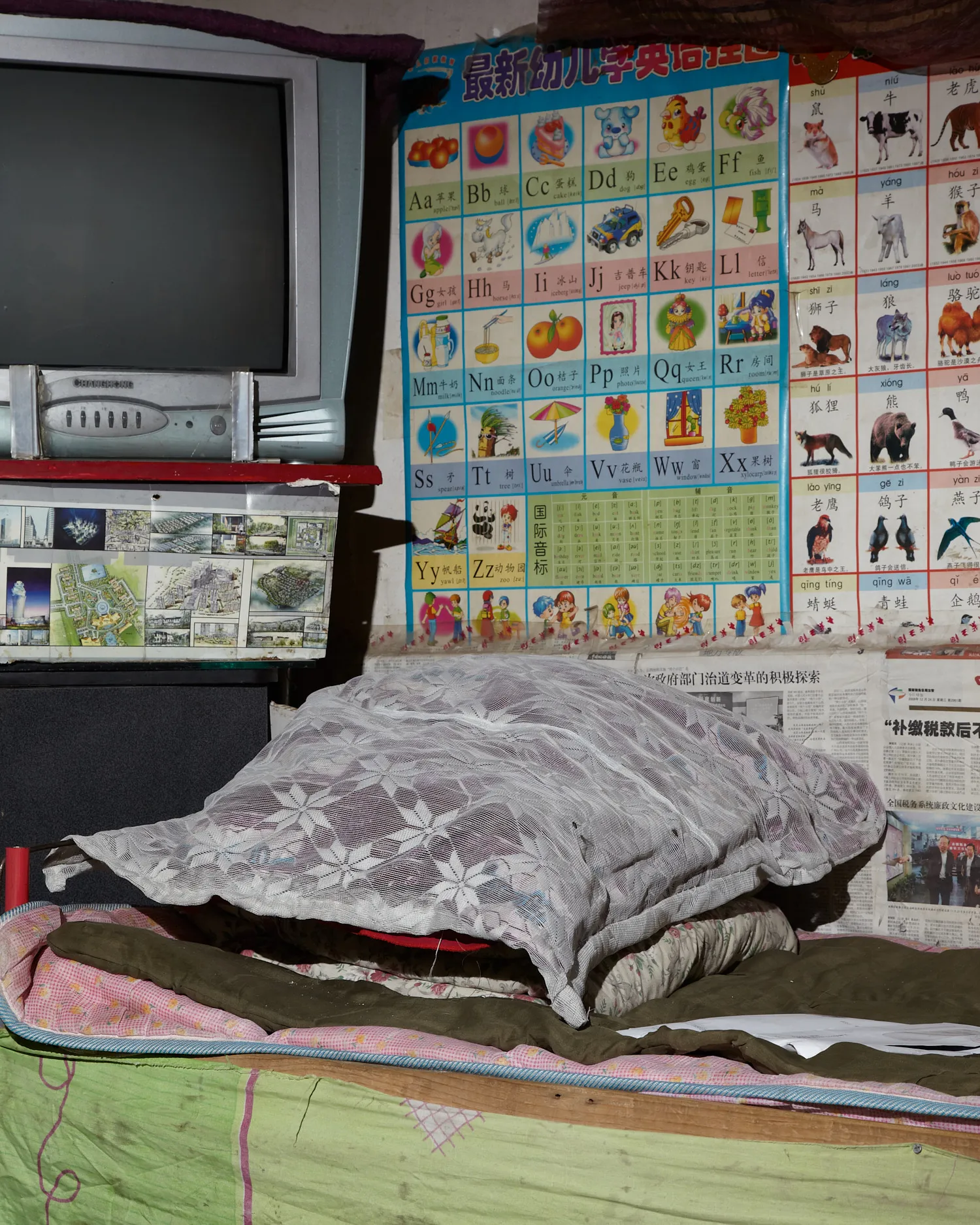

MADE IN CHINA is the result of Johan Nieuwenhuize’s artist in residency period at the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing in 2009. Nieuwenhuize took pictures in the homes of migrant workers in the area of Caochangdi and combines these still lifes with abstract pictures of the sky and self portraits.

The project was shown in solo exhibitions at the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing, in 2009, at Van Kranendonk Gallery and Art Rotterdam, both in 2010.

The book MADE IN CHINA was self-published in 2011 and contains a text by Hripsimé Visser, then conservator of photography of Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and an interview by Wim van Sinderen, then senior curator GEM/The Hague Museum of Photography. This interview can be read below.

MADE IN CHINA was made possible by the Mondriaan Fund and The Shareholders.

MADE IN CHINA

Interview on 17 March 2010 by Wim van Sinderen, senior curator GEM/The Hague Museum of Photography.

Wim van Sinderen: Your graduation work is substantially different from what you are currently doing.

Johan Nieuwenhuize: Back then I worked in a more serial manner. It was about developing a fixed concept: searching for a certain moment in different situations. Thereupon I combined these moments. In that way it became a collection.

WS: This exhibition MADE IN CHINA sort of resembles your exhibition ZELFPORTRETTEN (Selfportraits, June 2008, Van Kranendonk Gallery, The Hague). I can remember there were self-portraits, portraits, and photographs of junk and worthless objects, that you oddly enough call self-portraits as well. There now seems to develop some kind of continuity in your work.

JN: That was the project that brought me to China. I had made photographs at my parents’ house. They collect and keep many things. A lot of junk, but also books and pieces of fabric. Anything that in their eyes can come in handy or has a certain value. That varies. Those things pile up, mostly in stacks. I photographed them, because I found them weird and exceptional.

WS: We live in a consumer society. Anything that is half broken is thrown away.

JN: Not by me. That is why I call the photographs of objects self-portraits. My parents’ hoarding behaviour has had a great influence on me. On me personally, but also on my identity as a photographer.

WS: You have made some beautiful pictures out of it. I can remember a photograph of a stack of egg cartons (Self Portrait #010). A found still life actually. And your portraits, those are of course self-portraits. I can see that in this exhibition as well. I find you a great model for yourself.

JN: Thank you. It is quite handy.

WS: When you also possess a certain appearance or are able to look very different each time, that is a bonus. How do these self-portraits relate to the still lifes? They are two painterly genres. You mix them together.

JN: It shows that materials play an important role in my life. I am also interested in the role that things play in other people’s lives. How your identity is mirrored in the objects surrounding you. And what influence that exerts. For me personally that influence is very tangible. By combining self-portraits and still lifes, I am showing two sides. There is room for interpretation in the work. The combination may seem odd at first, but I think that the viewer will see the connection and give his or her personal interpretation.

WS: What you did in China is different from the previous series, but I do see the same concept with a different pretext.

JN: The combination of self-portrait and still life is the same. But the need to make self-portraits became very apparent to me in China. I was there as a Westerner. A tall blond young man with comparatively a lot of money and expensive gear. That difference forced me to take a stance with regard to my own position.

WS: For three months you were a guest of the Three Shadows Photography Arts Centre in Beijing. To me it would seem more obvious that as a photographer you would make some sort of documentary photography. It is a very photogenic country.

JN: Naturally it is all very attractive and unusual. In the beginning I did make that kind of photographs. But in the end I found it much more interesting to discover how people from a different culture associate with the materials that surround them. I wanted to take a step forward, to develop myself artistically. China seemed to be a good environment for that. Materials are ubiquitous and the consumer society experiences a mushroom growth. There are many people, migrant workers, who move from the country to the cities and who bring all sorts of things with them. To me that formed a parallel with my own experiences.

WS: In China there are extremely wealthy people who own the most hideous objects and there are very poor people. That is an interesting contrast that clamours for being made into an image.

JN: Well, I did not completely succeed in that, although I did plan on concentrating on that aspect. How do poor people deal with materials and how do rich people do that? What is the meaning of materials in their lives? I did make photographs at rich people’s houses, but I can identify less with them, because they attach a different importance to things. It is more fleeting and idle. Migrant workers are forced by their situation to deal with materials in a more inventive way.

WS: A reportage or documentary photographer does not need to have any feelings. He just has to make an image out of it. You say: “There has to be something of me in it, it has to be my concept, even if it is China, even if it is big, it has to have something to do with me”.

JN: Yes, I think so, but I never really think about that distinction.

WS: Are you more of an artist than a photographer?

JN: I think it has to do with the fact that I am looking for the personal. That makes it much more specialized. I am really searching for sculptures that say something about the way people deal with materials.

WS: And you manipulate that as well. You told me that you made Untitled #004 with wrapping material you found in the neighbourhood. We must consider that as a sculpture. In the exhibition you hang it next to Under the Fifth Ring Road #002 Dongba, Beijing, a picture of vegetables wrapped in thick blankets, which is a found sculpture.

JN: I find it interesting to make my position clear and not only showing the situation from the outside. I wanted to show that I am here and I am doing this. But in the end I have very seldom manipulated the situations in the still lifes. Untitled #004 is one of the exceptions. Most things I just came across.

WS: You did not stack the stones in Aomen Rd. #03. Shanghai?

JN: No, that was so wonderful about that situation. Eventually it is not important whether I did it or not. I try to show things in a way that it can be both one thing and another. The tap is a very good example. That photo is titled Temporary Solution. Caochangdi, Beijing. A temporary solution; that is what it originally was. Now it is still a tap with a plastic bag on it, but it can also be some sort of animal.

WS: Do you think that you were able to see this, because you entered as a foreigner? Or do you have a keener eye than the average person?

JN: It is a combination. I do think that as a Westerner in another culture I have experienced everything differently than if I were an Asian person. I had to restrain myself though, because you can easily fall into clichés and start showing all sorts of things that are not very interesting from a Chinese point of view: things that are quite normal actually.

WS: What were the reactions of the Chinese people to your exhibition over there?

JN: In China modern art has not been around for longer than twenty years. They have a very different attitude towards modern art. Collectors mostly buy Chinese art, not Western art. They like the spectacular and prefer a pink five metre high dinosaur to an intimate portrait. There is a lot of space there as well, so things have to be big to get noticed. The Chinese do not give very direct comments like the Dutch do. Sometimes you do notice that they find something less interesting or attractive and then they just walk away. The younger people though do ask critical questions: “Why do you combine such diverse subject matters?” or “Why do you photograph that junk?” That is not that obvious to them either.

WS: They did not say that you would discredit the country by only focussing on this aspect?

JN: Not during the exhibition. I did experience that people did not want to cooperate, that they said: “Go and photograph some junk in your own country”. And then I showed them pictures of my parents’ house.

WS: Were the authorities bothering you in any way?

JN: No, I have always felt free. But then again, I had money. As a Westerner with money you are in a very different position. Officially every exhibition is censured. In practice a blind eye is turned to many things. Unless you discredit China and it becomes a row, especially when it crosses the borders. Then it is quickly over.

WS: Have there already been more Dutch guests at Three Shadows Photography Arts Centre?

JN: As far as I know I was the first Dutchman. In any case I was one of the first artists in residence there. It took some getting used to on their part as well.

WS: Were you happy to return to The Netherlands after three months?

JN: After two months I wanted to go home. All the input became a bit too much, but after the opening of my exhibition there were only ten days left and then I really wanted to stay longer.

WS: In some of the self-portraits you are wearing designer clothes. Are these your own clothes that you had copied over there?

JN: I was fascinated by the Chinese urge of copying. That is why I had my clothes copied as accurately as possible by a Chinese tailor. For some of the self-portraits I copied the behaviour of Chinese people in these clothes, like in Self Portrait with a Chinese Copy of my G-Star Jeans. Caochangdi, Beijing. The trousers are a copy of my jeans. In that picture I copy the way in which the Chinese often sit. In Self Portrait with a Chinese Copy of my Matinique Shirt, Caochangdi, Beijing, in which I stand next to a railway line with my shirt rolled up, I am also wearing copied clothes and at the same time copying the behaviour of migrant workers. When it is hot they roll up their shirts. It cools them down. Because of all this producing and copying the exhibition is called MADE IN CHINA. That is something that has stuck with me from my childhood days; many things are “MADE IN CHINA”.

WS: You set up the exhibition as an installation. Like there was no way round this. The works are not hanging in one line, you made combinations with them. What do you want to achieve with this approach?

JN: I first copied the gallery in wood on a scale of 1:10. Then I printed all the photos 1:10 and started arranging them for four months before finally making a selection. At first the whole gallery was full but slowly it took its shape. When we started setting up the exhibition I put down the model and things went very quickly. But that was the result of four months’ work in my studio.

WS: Why do you do it that way? Has it got something to do with looking?

JN: It has got something to do with the fact that I want the exhibition space to be part of the work’s content. I have my photographs and that is the raw point of departure for the installation. There are actually two processes: I take photographs and on the basis of these photographs I make a selection. Which of the photographs are able to tell what I want to convey? Thereupon I will design the installation: the space and the spot where the photograph will hang in that space. The height at which the work hangs is of great influence on the viewer. I want to use that. I want you to stand in a space and look at the work from a certain angle and distance and at the combinations I have made.

WS: It does work. But one is not sure what it depends upon. Maybe it is this four-month process that you have gone through for us that makes it all look so self-evident.

JN: My motive is to have the viewer look at things in a different way. The height on which things are standing or hanging in real situations is a sort of guiding principle. I find it pleasing when people look at things from the same angle as I did, when I took the picture. It has a lot to do with playing it by ear.

WS: What is your opinion on someone buying a work and doing his own thing with it?

JN: I don’t mind that, but I do find it annoying that the installation will no longer be there. That is why I photograph it and have it filmed. That is also one of the reasons for making a scale model. In that way I can hold on to the installation. My motive for doing that has been influenced by my parents and their holding on to materials and saving everything that may one day prove of importance. For me that translates into taking pictures of things that I find important.

WS: Would you be prepared to be in full charge of the combination of your photographs, in the sense that it can only be sold as a whole with instructions for hanging?

JN: I think it is a wonderful idea, but it is not what I aspire to. It is fine with me that people buy one photograph, because they think it is beautiful and subsequently hang it on a different height in their home. No problem whatsoever.

WS: The exhibition seems of utmost importance to you, because you are able to make a statement. It is an environment, where one can walk into your vision and notions.

JN: To me it is important that seemingly unimportant things can turn into significant desirable objects by the way I photograph and present them. And that they form a clear connection to my position. This exhibition form is very helpful in that sense.

WS: What is your next step?

JN: I am currently making photographs of skies. That is also a way of saying something about my position. At a certain place, at a certain moment I pointed my camera up and took a photo of the sky. I am now looking for moments that are less non-committal. These are events that have exerted a great influence on the development of my identity; for example the fall of the Berlin wall or 9/11. These important political events have helped shape my identity. And I can remember them happening. I have witnessed 9/11, be it from a distance. Everyone of my generation has the feeling of having witnessed many events, because it could be seen on television or through other mass media. This indirectness I find very interesting; to deal with the medium in a different way, to make a representation of reality in another manner.

This interview between Wim van Sinderen and Johan Nieuwenhuize took place on Wednesday 17 March 2010 in Van Kranendonk Gallery in The Hague on the occasion of the exhibition Made in China.