Jelle Bouwhuis on The Bubble

Johan Nieuwenhuize – The Bubble

By Jelle Bouwhuis

“Technological developments and their impact on society are becoming an increasingly important element of my work. How filter bubbles make our online world smaller contrasts sharply with the uninhibited positive ideas about freedom and democracy from the early days of the Internet.”

Johan Nieuwenhuize

Social media, search engines, games and websites are becoming increasingly more adept at predicting our behaviour. They know what we are going to search for before we start searching, what we want to see before we look and, above all, know what we can buy before we have spent any money. They try to trap us in a filtered environment that simplifies our lives as consumers but, at the same time, makes our actions and thoughts as predictable as possible. Visualisations of Twitter traffic, for example, make painfully clear that leftist twitterers primarily follow leftist twitterers and right-wing twitterers primarily right-wing twitterers. Academics follow academics, car enthusiasts follow car enthusiasts, chefs follow chefs, and so on. Of course, it’s not possible to follow everyone, but social media sometimes appears to be a medieval guild system with closed networks and not unlike the pillarisation that held the Netherlands in its grip until after World War II. The fact that everyone can ‘live’ in his or her own bubble apparently appeals to a deeply rooted desire for a sense of safety and security.

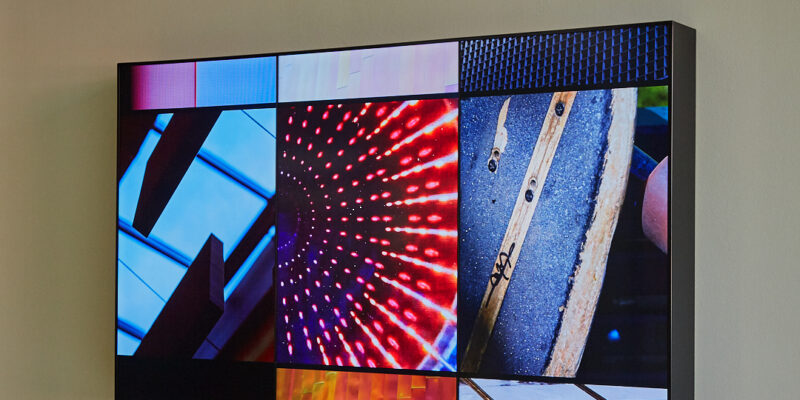

Johan Nieuwenhuize’s The Bubble responds to that oh-so-human filter that has been strengthened by the Internet. His work does this specifically with regard to the social community at The Hague University of Applied Sciences (it was created on the occasion of the school’s 30th anniversary). Continuously changing photographic images are generated on three connected monitors, originating from a total of 717 pictures. These pictures were taken by Nieuwenhuize, who studied Industrial Design Engineering at The Hague University of Applied Sciences before enrolling in the art academy. He asked a diverse group of eighty (current) students a series of questions in order to gain insight into their lifestyle, such as their favourite shoe brand, their source of news, their favourite spot at the school, etc. He then used their responses to create and select the images.

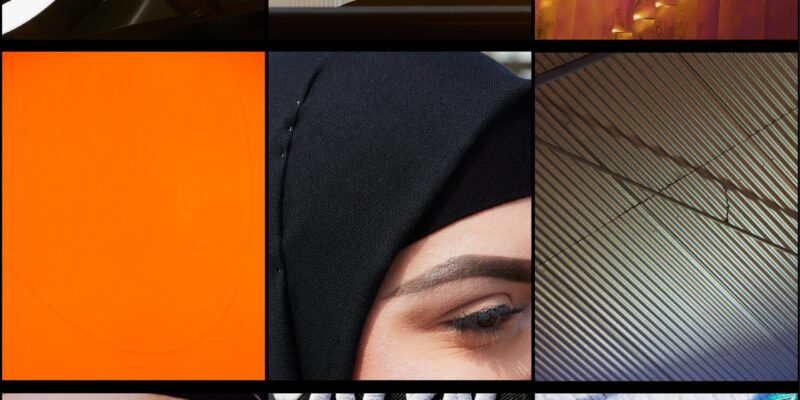

The result is in typical Nieuwenhuizian style. In other words, all of the photographs were shot in the same format, giving the totality a sense of comparability. The generic aspect is reinforced by his preference for images that are not culture-specific and are difficult or impossible to trace back to a specific person or environment. This is typical of Nieuwenhuize’s approach. Since 2009, he has been working on a series of photographs entitled Collected Memory taken from the sky above well-known disaster sites like the WTC in New York, Utøya island in Norway, Tiananmen Square in Beijing and the Bijlmer neighbourhood in Amsterdam Zuidoost. The fact that he takes these pictures during the same months, days and hours that a tragedy took place at these locations says something about his understanding of the concept of remembrance. It is not the physical characteristics of such sites that are the focus of his work, but purely their reference, such as an abstract picture with a title. This is enough in itself to reactivate the collective, medial memory.

The totality of photographs in The Bubble can perhaps be described as a portrait of an era at The Hague University of Applied Sciences, though the individual pictures are actually just as abstract as the blue skies above a disaster site. Pictures of architecture and architectural details in particular dominate his work, though the collection also includes other types of footage. The pictures can be classified into various groups, such as pictures showing food, footwear, accessories, sports, advertising images, news images, entertainment and shopping locations. Nieuwenhuize devotes considerable attention to detail and composition and some of the pictures may evoke various associations, but are relatively generic in terms of content. Unlike the pictures in The Hague University of Applied Sciences collection that focus on the individual, such as the student portraits by Beat Streuli, the celebrities by Anton Corbijn or even those of artists like Wijnanda Deroo and Bertien van Manen that capture entire interiors, Nieuwenhuize refrains from such specificity. In that respect, his work is more closely related to that of Jan Adriaans or Andreas Gursky in the school’s art collection. They are all photographers engaged in what French anthropologist Marc Augé referred to in 1992 as non-place: buildings like hospitals, train stations, airport terminals and schools that are often so similar, also to each other, that you can no longer tell the difference, regardless of where in the world they are built. But whereas Gursky’s image of Hong Kong and Andriaans’ portraits of garages are largely constructed or staged, Nieuwenhuize portrays reality as it really is. He primarily constructs images through selection, framing and the use of light. And through the large volume of images, he does not focus on a single monumental image, but on the massiveness of the image, on the ‘bubble’.

Nieuwenhuize – in collaboration with neuroscientist and machine learning researcher Robin van Emden – were posted on the 717 photos on a website, where those affiliated with The Hague University of Applied Sciences could state their preference for particular images. This helped further fine-tune the school bubble. These preferences are displayed on the monitors. As viewers approach the monitors, the selection changes. An algorithm connected to a motion detector creates a constellation of images at that moment that are not part of the specified preferences. In other words, an anti-bubble is created. In practice, it is difficult to distinguish between the two. What matters is that a different constellation of images is continuously shown for which the university of applied sciences community has a certain affinity, at least in theory or, conversely, an aversion.

In spite of the affinity that is factored in, the image still causes a bit of friction. Literally. That’s because Nieuwenhuize took the pictures with an aspect ratio of 5 to 4. This is the format of classic photographic negatives, whereas digital SLR cameras have an aspect ratio of 3 to 2 and monitors usually have an elongated ratio of 16 to 9, the panoramic format used for motion pictures. In other words, Nieuwehuize’s pictures do not fit the monitors properly, even when displayed vertically. This is why two edges can be seen on each monitor, each with a different ‘bubble’ picture from the collection.

Nieuwenhuize’s work is a welcome addition to the art collection of The Hague University of Applied Sciences. The location on the Laakhaven, built soon after Augé introduced the concept of non-place, is design without any ethnic, religious or regional-historic characteristics (like The Hague City Hall from 1995). This was soon after the fall of the Iron Curtain, a time of unbridled and optimistic globalism in which such distinctions were no longer regarded to be relevant, at least not in an internationally oriented city like The Hague. The creation and display of an art collection became a means to create distinction and, interestingly enough, in spite of globalisation, almost exclusively Dutch – and a few other Western European – artists were chosen. Looking back at the collection, it is striking how classical the photography is: the works hang on the wall in monumental format like paintings. They were collected at a time when the ubiquitous bombardment of images found on the Internet, the mobile phone camera, the selfie culture and the Instagram page did not yet exist. With the addition of Nieuwenhuize’s The Bubble, the school is stepping into the present: the work is interactive and monitor-oriented. At the same time, Nieuwenhuize problematises the notion of identity by creating a unique bond with the diverse school community. What does identity mean as a notion if it is generated and constructed continuously by invisible algorithms from megalomanic Internet companies that are not tied to a specific place? Compared to this invisible steamroller, The Bubble offers us perhaps a better grip than you might think at first glance.

Jelle Bouwhuis is a curator, publicist and art-historical researcher